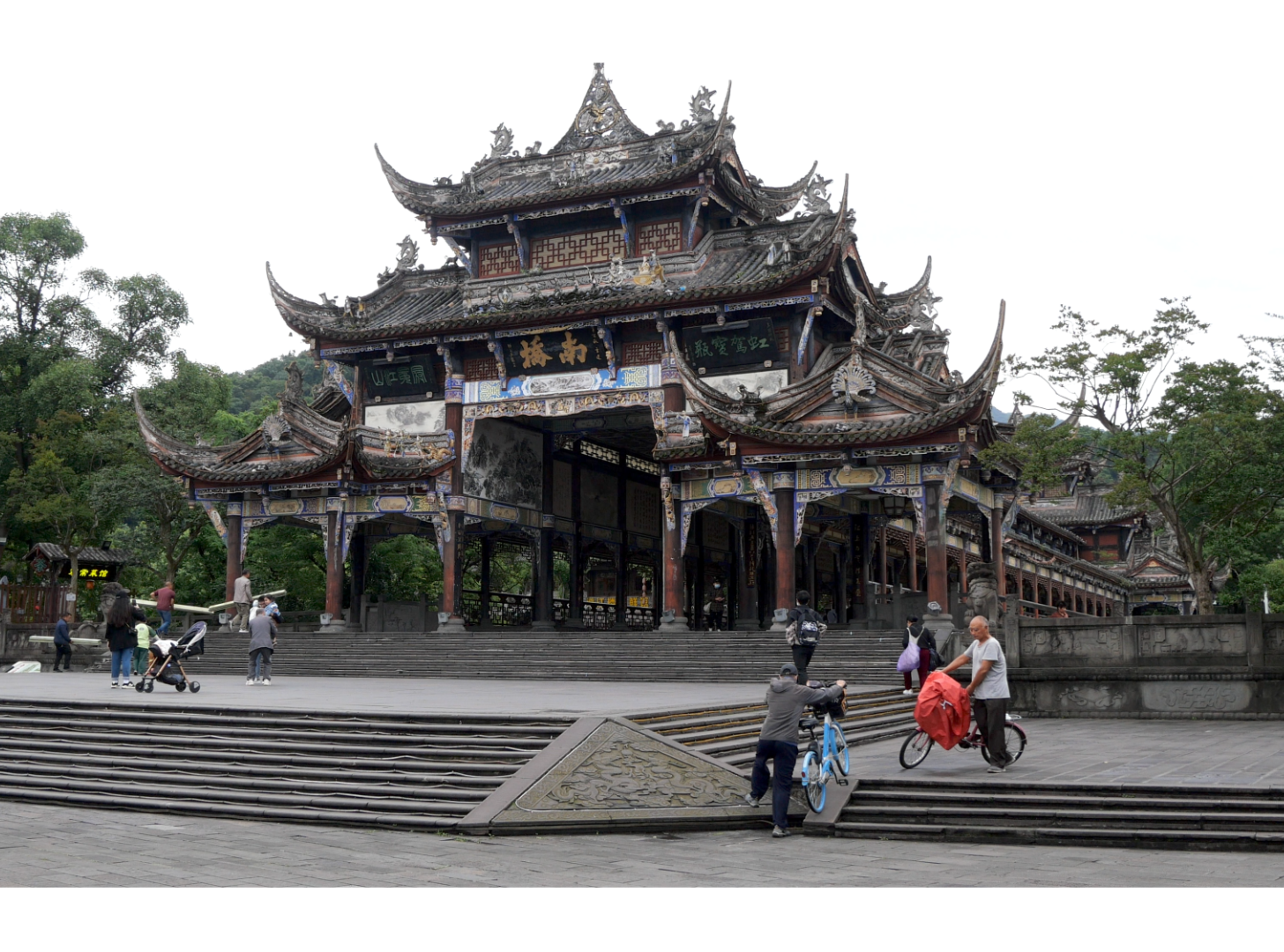

I lean my loaded touring bicycle against the intricately carved handrail of 南桥 nánqiáo, South Bridge, and feel the cool spray from the milky blue water thundering below. Closing my eyes, I can almost taste its glacial origin, and the journey it took through the crags and falls of the alpine Mín Valley to get here.

It’s a cloudy Saturday morning in 都江堰Dūjiāngyàn, a city of 320,000 people 60km northwest of Chéngdū, and a smattering of tourists are wandering the bridge already. All eyes and cameras point upstream to Bǎopíngkǒu, ‘Bottleneck Mouth,’ the 20 meter-wide, 80 meter-long split in the yùlěi mountains through which the river is gushing. While it looks natural, it was actually hacked open by workers using only hand tools and controlled fires over an eight year period, starting in 256 BC.

Along with ‘Flying Sand Weir’ and ‘Fish Mouth Levee,’ this waterway is part of the Dūjiāngyàn Irrigation system, masterminded by the great hydrologist李冰Lǐ Bīng. It provides a transport route and drinking water to the Chéngdū Plain to this day.

I take a half-flattened sandwich out of my pannier and eat, savouring the atmosphere of epic history while trying to get as many calories into my body as possible: this is where the fertile plains meet the Tibetan plateau, and all roads on from here are steep.

Pedalling west through town, I feel a flicker of nervous excitement. It doesn’t seem entirely normal to be cycling alone: Tamzin and I discovered bike touring together, and tend to do it that way. But while we’ve been dying to get out of the city as a pack, the dogs’ training process is ongoing, so this month we’ve decided to set out on our own adventures.

Steel shop shutters are clattering open in the crooked backstreets as I trundle past, breathing deep to relish the cool, moist air. After a few labyrinthine twists I reach the 250-meter-long Qīngchéng Bridge, and feel exhilaration – or is it vertigo – as the main, wide body of Mín River falls away beneath me. Across the valley, through the fog and drizzle, the dark green humps of Qīngchéng mountain range emerge, among which the doctrine of Daoism was first written.

I pedal hard towards the mountains, my gaze turned down to look through the rapidly-flitting bars of the barrier to my right. The roiling currents, whirlpools, sprays of foam and jagged boulders are mesmerizing, and I slow my pace to further appreciate this hydrological feat.

Built by tens of thousands of workers placing zhūlóng, cylindrical ‘pig baskets’ filled with rocks in the river, Lǐ Bīng’s system supplies irrigation channels with water during dry season, and flushes it away during the rainy season. Through preventing silt buildup along the Mín river, Dūjiāngyàn is credited with transforming Chéngdū into 天府之国tiānfǔzhīguó, ‘The Land of Abundance.’ It’s the perfect example of fēngshui: the art of studying the natural environment, while harnessing the opposing forces of yīn and yáng.

I snap out of my tranquil state when the cycle lane merges abruptly with the road at the end of the bridge, causing me to swerve into the traffic. Riding a slope down into a series of newly built housing developments, I check my map and continue west, passing a landscape of green construction netting punctuated by old villagers still tending vegetable patches amid the rubble.

It’s fair to say that priorities have shifted since the days of Lǐ Bīng’s masterpiece. While massive rollouts of ‘green infrastructure’ are attempting to reinsert nature back into urban environments, many modern developments along the Min River seem to fly in the face of that era of careful planning. While the list is long, none do this quite so dramatically as Zǐpíngpū, the 760-megawatt hydroelectricity dam looming just a few miles upriver.

Despite being touted as a source of ‘clean energy,’ the megaproject was always controversial. Campaigners railed against the risk of “damaging both the ancient waterworks’ ability to function as an effective irrigation and flood-control system”; harming the river ecology and forcing the relocation of 40,000 residents from the 18km2 area flooded by the reservoir. It’s possible that UNESCO stripped Dūjiāngyàn of its “Natural Heritage” status based on these factors alone. But most alarming of all was the newly-amassed water body’s “close proximity to a seismic fault line…”

I consider heading north and repeating the visit we made to the reservoir last year, but it lies within Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous County. Due to a recent covid outbreak in Shànghǎi, I must stay within Chéngdū municipality to avoid being pinged on my phone and having to quarantine when I get back.

So I keep riding west, and the construction sites quickly fall away to be replaced by the first of the Qīngchéng foothills. Flanked on my right by a steep bank of larch and pine, I feel a deep calm descending, as if a pressure valve has been released.

At a gravel car park, several cartoon-style panda statues are arranged in martial arts poses before a gigantic sign that reads Panda Valley. A few stationary coaches are releasing clusters of tourists, and as they walk nonchalantly towards the ticket booth my mind goes back to Zǐpíngpū dam.

At 14:28 on 12th May 2008, just two years after the Dam’s completion, an 8.0-magnitude earthquake struck in the nearby town of Wènchuān. An estimated 90,000 people were killed, 374,000 were reported injured and a potential 4.5 million people were made homeless. It was a truly catastrophic event which, although its causes remain shrouded in controversy, unified the nation as much as it traumatized it.

The impact on nature was dire, as the natural corridor in which 80% of China’s giant pandas live was heavily fragmented by landslides. Unknown numbers of wild pandas, as well as several living within the Wòlóng panda center five miles from the epicenter, were injured or killed.

While efforts to locate, rescue and re-home human survivors of the disaster took precedence, the knock taken by China’s most iconic threatened species was also high on the agenda. According to Edwin Schmitt and Shang Yuan, conservationists argued that “only a massive effort to remove or limit human impact from this region, where 170,000 people still live, can help to establish corridors for fragmented panda groups to begin interacting.”

Turning their attention outwards to “the new trend in biodiversity conservation described as rewilding,” ten years after the quake in 2017, the government created Giant Panda National Park, a vast protected area stretching across parts of Sìchuān, Gānsù and Níngxià provinces.

Standing at the edge of Panda Valley, I’m sure that this particular ‘Breeding and Research Center,’ as it’s labeled on my map, plays a role within the broader context of reintegrating giant pandas into the Chinese landscape. However, I’ve seen photos online of tourists posing with subdued looking bears and even handling cubs, and I have no desire to impose my presence on wild animals in this way. I ride on.

Occasional slate-roofed wooden houses dot the road for the next mile or so as I climb steadily in altitude. A right turn takes me beneath a dense forest canopy, quickly shutting out both sound and light, and the intense fug from a nearby woodburning stove hangs in the air. I pedal hard, trying to get momentum on the suddenly steep incline and quickly become exhausted; burned-out by a sprint my body wasn’t ready for. Switching to a Sherpa-style zigzag pattern and dropping to the lowest gear, after some time I manage to fall into a rhythm.

Through gaps between dense bamboo clumps to my left I see a deep valley, topped by a vista of irregular peaks creating a saw-like ridge. I assume it to be Qīngchéng Ridge: the karst landscape of porous limestone, caves and sinkholes which marks the border between Chéngdū municipality and Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous County.

Giant pandas once ranged throughout all of East Asia. In that heady hill-cycling state between agony and ecstasy, I wonder if the ridge was once the arena of their courtship rituals, in which females drag their scent across miles of undergrowth, pursued by rival males that snarl, fight and sometimes kill one another to attain higher ground. Females often flee up trees and are held hostage for as long as a week by the victorious male – a process which it’s believed may trigger the final stage of estrus.

Cresting a pass and freewheeling downhill for a while, I’m struck by the challenge and reward that rewilding poses. To liberate pandas here would be to welcome them into the public consciousness not as fluffy cartoon characters with stunted sex drives, but bears: powerful, solitary omnivores who brave the Chinese winter, crack bamboo with their powerful jaws and occasionally “break into livestock pens and consume goats and sheep.”

Four or five kilometers pass in slow, grinding fashion upward and around hairpin bends, until I finally arrive at Long Feng Village. The small township serves as a base camp for hikes up to the peak of Zhào Gōng Mountain, named after General赵公明Zhào Gōngmíng, the legendary sage and Daoist god of wealth.

Sitting on a roadside patch of grass, I take out my stove and fix some noodles and coffee, preparing for the final climb along 森林康养绿道sēnlín kāngyǎng lǜdào, ‘Forest Health Greenway:’ a new cycle track encircling the mountain’s protected core. This part of the village is largely comprised of squat concrete buildings built into the mountainside. Whatever damage it sustained during the Earthquake is no longer visible, and a rustic restaurant is serving snacks and beer to a cheerful group of mountain bikers sitting outside.

I zigzag and struggle up the hill alone for the final stretch, accompanied only by the sound of my own breath and a redbilled blue magpie that swoops to-and-fro in front of me. Businesses aren’t excluded from this zone but they are less frequent. As I climb, I pass occasional, basic lodges positioned over mountain streams, drawing water for their kitchens via bamboo standpipes.

An indeterminate amount of time later and I must have passed the famous peak without noticing, as I’m freewheeling downhill with the wind chilling my sweat. Orchards of fruit trees, cabbage patches, village graveyards and Buddhist shrines pass by in a blur as I pump the brakes rapidly. On this side of the pass the legacy of Wenchuan Earthquake appears regularly, in the form of sunken guesthouses, collapsed foot bridges and miniature ghost towns, apparently intact but completely abandoned.

I stop for a while beside a cracked swimming pool exploding with brambles, and it looks as if nature is hurrying to claw back the space taken up by this out-of-place artifice. I’m reminded of George Monbiot’s essay Accidental Rewilding, in which he asserts that “most of the rewilding that has taken place on Earth so far has happened at the expense of the human population.”

When nature has made a fightback into human territory, it’s usually been the result of war, famine or other catastrophe leading to an absence of humans. This has also been a consistent theme throughout Chinese history, as well as an important cautionary chapter in the story of Dūjiāngyàn irrigation system.

In their fascinating paper ‘Retreat of the Human,’ Edwin Schmitt and Shang Yuan retell the tumultuous, bloody final years of the Míng Dynasty (1368-1644 AD), in which war, famine and disease caused a rapid depopulation of the Chéngdū Plain. When the essential practice of annual dredging, repairs and maintenance of Dūjiāngyàn known as岁修suìxiū collapsed, in 1619 “hundreds of miles of canals in Chéngdū Prefecture began suffering a severe water deficiency.”

This made rice farming untenable, and the subsequent land abandonment led to huge swathes of farmland across Sìchuān running wild. Terrifyingly for the survivors, this provided optimal habitat for tigers, who began making their way back into villages and towns. The fierce confrontation between the two species lasted several years, with deaths from tiger attacks a daily occurrence in the province. Previously unseen behaviours were recorded, such as climbing up buildings and stalking people from the rooftops, and even “approaching and boarding boats by swimming.”

The situation was so dire that The Liuli Waizhuan, written by Han Guoxiang, records that “half of Sichuan’s people died because of warfare. After this, half of the survivors died because of famine, and the other half of the survivors died because of tigers. The people cannot bear this suffering anymore.”

Many literati at the time saw the tiger attacks to be the result of moral failure which would eventually cause the collapse of human civilization. One who clearly believed this to be the case was poet Shen Xunwei, who hid in an area occupied by the new Qīng army after losing his father during a famine-induced riot:

Sixteen autumns have passed since I left Chéngdū,

Who can help me cope with my myriad emotions?

Chéngdū has been occupied by wildgrass for ages

Elk roam among the grain fields

God desires to obliterate the legacy of the Hàn Chinese Empire,

But I alone am powerless to defend it from outside forces

Although, in past and present, a civilisation’s rise and fall is a common affair

I still cannot understand how such a thing could befall Sìchuān.

Lying in my tent listening to the rapid-fire hoots of a collared owlet, I consider the paradox of wishing for a resurgence of wild nature, all-the-while celebrating Lǐ Bīng’s achievement of subduing the destructive forces of the Mín River.

However, it’s important to remember that seeking to make space for wild nature is not born out of contempt for ‘civilisation.’ On the contrary, it is based in an understanding of planetary boundaries that we must respect for civilisation to thrive.

As I drift off to sleep, I hope that we are now entering an era in which rewilding takes place not as a result of catastrophe, but of the type of custodianship and care that Lǐ Bīng would be proud of.

Share this post